“I couldn’t achieve my numbers,” rues Malhotra, who declines to share the financials but lists out the blunders.

First, the brand was taken in by a booming quick service restaurant (QSR) market. India’s burgeoning middle class — an estimate by IBEF pegged it at 267 million — economic growth of 7 per cent-plus, and a projected CAGR of over 22 per cent for QSR by 2021 suggested that this was the place to be. “These are common perceptions with which foreign brands come to India,” says Malhotra.

Enthused by the prospects, Barcelos went out on a limb, opting to choose high-street areas with high rentals to grab eyeballs. The strategy bombed as they weren’t the only brand to think that way; the high street soon got overcrowded with outlets targeting the same set of consumers.

What’s more, unlike Western nations where consumers are used to grilled food and barbecue, India, Malhotra reckons, was not ready for Barcelos’ Mediterranean rolls and kebabs. “Indians still love roti, dal, curry and nautanki food,” he says, adding that acceptance of foreign cuisine is still confined to a small section of population. Result: the brand had to rejig its India plan, which meant smaller stores, more food innovations and moving out of high streets.

The Burger Bulge

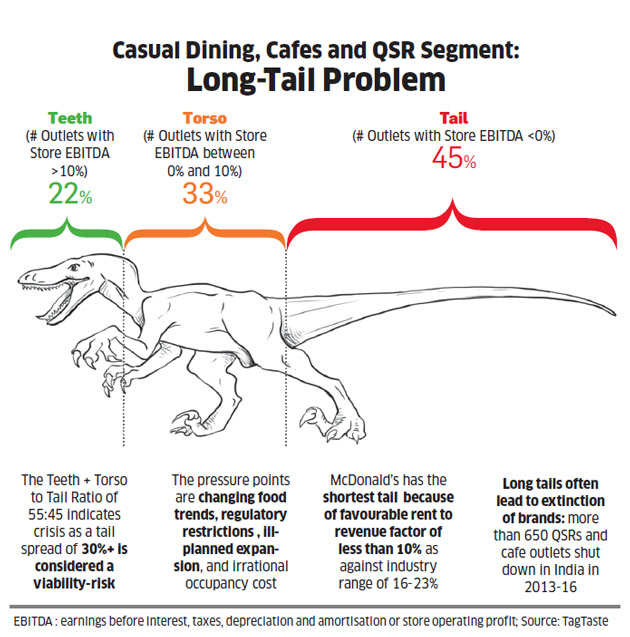

Barcelos isn’t the only foreign brand that got its India plan wrong in the last few years. Over 650 QSR and café outlets shut down between 2013 and 2016 in India, according to a study done by Tag-Taste, an online community for food professionals. The survey covered 2,050 outlets in all formats across the country between last November and May.

…but then why are global QSR brands hurting

What is more alarming are the operational metrics. Over 45 per cent of the QSR and café players, the study claims, had a negative EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation). Some 33 per cent logged an EBITDA/revenue of between 0 and 10 per cent, and only 22 per cent had a margin of over 10 per cent. The EBITDA margin is a measure of a company’s operating profitability as a percentage of total revenues.

The short point: close to half of the industry was financially unviable.

Changing food trends, regulatory restrictions, ill-planned expansion and irrational occupancy cost are some of the pressure points that the industry has been grappling with, concludes the study.

Even if measured on the parameter of same store growth (SSG) — which indicates a brand’s financial health — QSR on the whole has been faring poorly. Take, for instance, the bellwether of QSR, Domino’s, with 1,127 outlets till May. SSG dipped by 7.5 per cent and 2.4 per cent for the fourth quarter of 2016-17 and the entire fiscal year, respectively. That’s from a high of 19.8 per cent in the second quarter of 2012-13. Operating revenue too was flat in the fourth quarter.

Standalone Restaurant Market is Huge

Shyam S Bhartia, chairman of Jubilant FoodWorksBSE 1.46 %, which runs Domino’s and Dunkin’ Donuts, acknowledged the grim reality. Fiscal 2017 was a year, he said in an earnings presentation, “that tested our mettle and posed unprecedented challenges. As a result, our topline growth was adversely impacted in the (fourth) quarter and the year”.

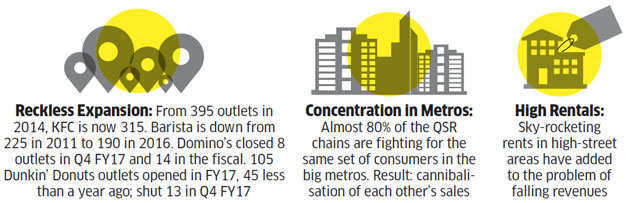

In its latest research report on Jubilant FoodWorks in May this year, Edelweiss BSE -0.05 % points out how the company is taking corrective measures. It has hired AT Kearney to rationalise costs, is shutting down stores — 13 Dunkin’ Donuts and eight Domino’s stores in the fourth quarter of fiscal 2017 — and reducing employees per store from 25 to 22, thereby bringing down staff costs by 2.5 per cent year-on-year. The plan is to cut the losses of Dunkin’ to half in the current fiscal. (Last fiscal, Dunkin’ closed 20 outlets.)

The sombre mood of the QSR industry is reflected in the store-opening guidance by Domino’s: 40-50 outlets for the current fiscal, sharply lower than past three years’ average of 135 stores, points out the report. Domino’s declined to comment on the story, citing the silent period.

Charred on the Grill

Store rationalisation is the buzzword at American chicken biggie KFC, too, which is down from a high of 395 outlets in 2014 to 315 now. Compare this with the target that Yum! Brands, which owns KFC and Pizza Hut, reportedly set in 2014: 2,000 outlets by 2020. Last year, Yum had 661 outlets, according to Euromonitor, a consumer markets research firm. Revenues too took a beating, from Rs 1,888 crore in 2014 to Rs 1,567 crore last year.

Rahul Shinde, managing director of KFC India, explains what went wrong. Through 2012-14 the QSR category, including KFC, focused on expansion, some of it indiscriminate, and not sustainable in the long run. Starting 2014 and the early part of the following year, the entire industry was affected. While some of the factors were external and reflected the overall industry sentiment, a slowdown in eating-out spends, pressure on rentals and operational efficiencies added to the woes. “Consequently, KFC was among the first few QSR brands to get affected,” says Shinde. The crisis pushed KFC to course-correct.

The brand tempered its bullishness, went to the drawing board and focused manically on reorganising the business. Costs of consumer acquisition were slashed and offers like BOGO (buy one get one) were done away with.

Instead, ways to create everyday value were devised, like a 5-in-1 Box (rice & gravy, chicken, wings, choco pie, cola). Then, rather than just weekends, a midweek band was created.

“Weekly offers like Wednesday Specials helped build footfalls,” says Shinde. He claims the results are showing, with the brand posting three consecutive quarters of SSG growth and six quarters of sequential growth.

Shinde, though, isn’t popping the champagne. Reason: the fickle nature of consumers and industry regulations. For instance, the Supreme Court order banning liquor outlets within 500 metres of state and national highways came as a bolt from the blue, and many QSRs serving liquor had to shut down in top cities. The SC allowing highway denotification within city limits earlier this week came as a belated breather for these outlets.

Regulation may be out of its control, but what the QSR industry can put a lid on is oversupply and reckless expansion. Over the last three years, QSR has been hit by a tsunami of foreign brands. Burger players such as Burger King, Wendy’s, Carl’s Jr, Johnny Rockets and Fat Burger and pizza brands such as Debonairs, Eagle Boys and Sbarro flooded the Indian market — all around the same time.

American burger chain Johnny Rockets opened its first store in India in January 2014 and planned to roll out 30 stores by 2020. Now, after three and a half years of opening, the burger brand has just five stores. Californian burger brand Carl’s Jr, which made its India debut in August 2015, has four stores in two years. The original target was 100 stores in 10 years.

“The current QSR scenario definitely looks very grim,” says Sam Chopra, chairman of Carl’s Jr India. High rentals, an unfriendly licence raj, corruption and demonetisation have dampened cash spends. “This gloom and doom in the market have led to conservation of capital,” he says.

Early this week, Carl’s Jr rolled out its cheapest offering at Rs 39. Earlier, the cheapest burger was priced at Rs 89. Marketing gurus will term that a response to downtrading, or consumers looking for cheaper options. “One needs to follow the 3 Ps of patience, perseverance and passion to sustain in the long run,” says Chopra.

Food experts trace the origin of the present-day crisis to 2008 when investors were high on funds and operators were brimming with high-adrenaline optimism of co-creating brands that would break the bank. A lot of money, reckons Ravi Wazir, a hospitality business consultant, was available to the F&B industry, particularly QSRs, who were the poster boys of the business, from private equity firms and high net-worth individuals.

Why it May Be Advantage Standalones : As consumers get more evolved in taste, they show inclination for standalone formats

It was believed that all things F&B would turn out millions, guaranteed. Unfortunately, little to no due diligence was done back then as to whether or not this was doable, adds Wazir, author of Restaurant Start-up: A Practical Guide.

A Complex Market

In 2011, signs of trouble began to emerge. Early investors realised that they were not getting the returns they expected or were promised. “They became cautious,” says Wazir, adding that many still believed in staying put, hoping for a turnaround.

This was the first lot that realised that the Indian market is far more complex than they had imagined. For the next four years, till 2015, new investors and brands kept coming. “This is when the last lot of them began experiencing what their early counterparts already did in 2011,” says Wazir. With each sub-market, at times even within the same city, responding differently to a brand, and behaving in an unpredictable manner, QSR brands found it hard to execute their vision of scaling up, as quickly and as successfully as they had imagined.

American fast food restaurant chain Wendy’s, which entered India in May 2015, saw the signs quite early. “It’s a simple story playing out in India ¡X of supply exceeding demand,” says Jasper Reid, director, Wendy’s & Jamie Oliver Restaurants. While consumer income and disposable income have been growing, the portion of the wallet for QSR players has not been growing at the same pace.

Another trend that might have impacted the business is convergence of food categories. A couple of years back, says Reid, coffee and QSR were seen as distinct categories.

No longer. “Wendy’s biggest hot beverage is homemade masala chai,” he points out. This results in a burger chain competing with a Cafe Coffee Day, or any tea brand or local chaiwallah.

“It’s an enormous battle that everybody is fighting to get hold of the customers’ heart and mind,” adds Reid. QSR has become a borderless segment where millennials easily move across brands. Wendy’s has scaled down its presence from four outlets to two.

The biggest learning for the brand, Reid reckons, is going slow and rejigging the growth strategy. The notion of having large outlets of 2,500-3,000 sq ft is a thing of the past. “It won’t work in India now,” he says.

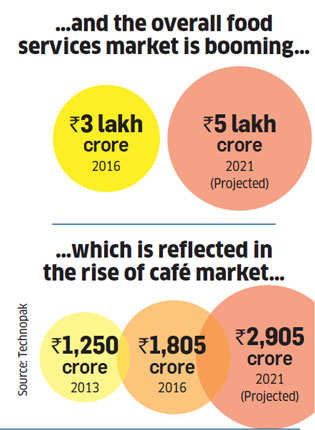

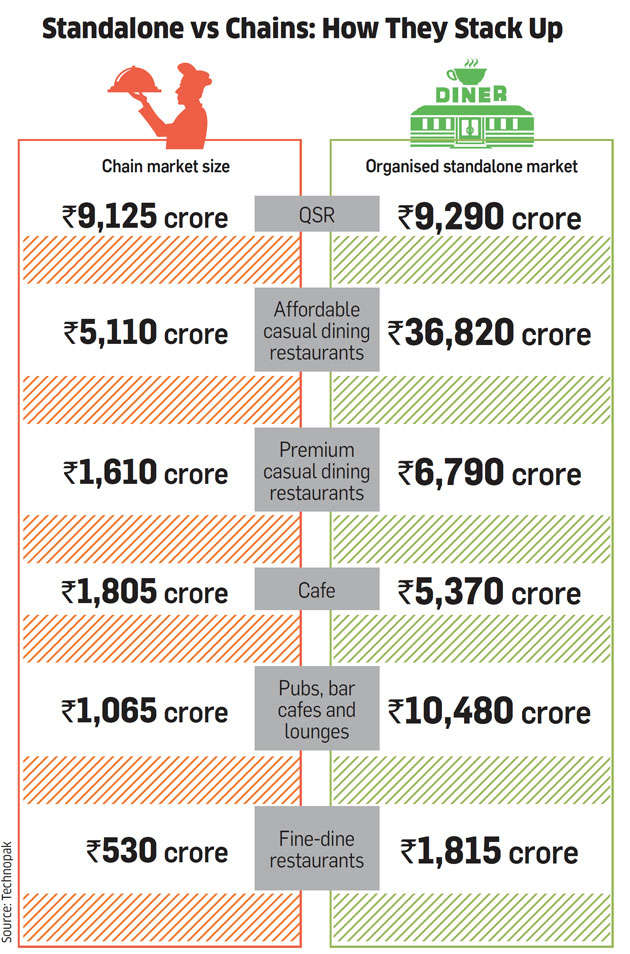

Saloni Nangia, president of retail consultancy firm Technopak Advisors, points out that with most brands concentrated in top cities, cannibalisation of sales is the order of the day. Nangia maintains that the consumption story of India remains intact. The QSR market, pegged at Rs 9,125 crore last year, is likely to touch Rs 24,665 crore by 2021. The overall food services market too is projected to boom: from Rs 3 lakh crore last year to Rs 5 lakh crore in 2021.

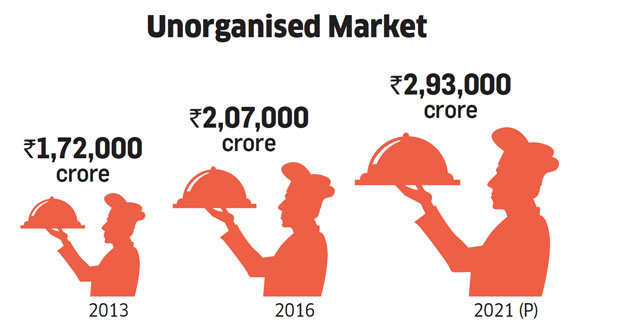

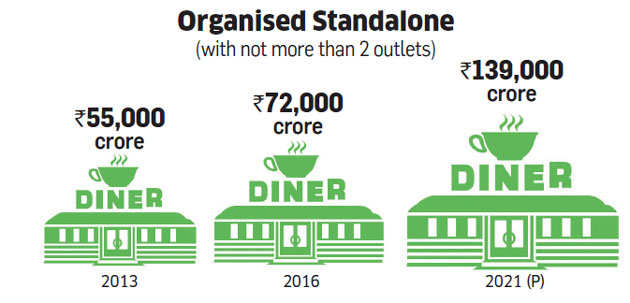

QSR chains, meanwhile, got hit from another quarter: standalone organised restaurants, brands with two or less outlets. Local food entrepreneurs gatecrashed the QSR party by focusing on providing wholesome experiences to consumers.

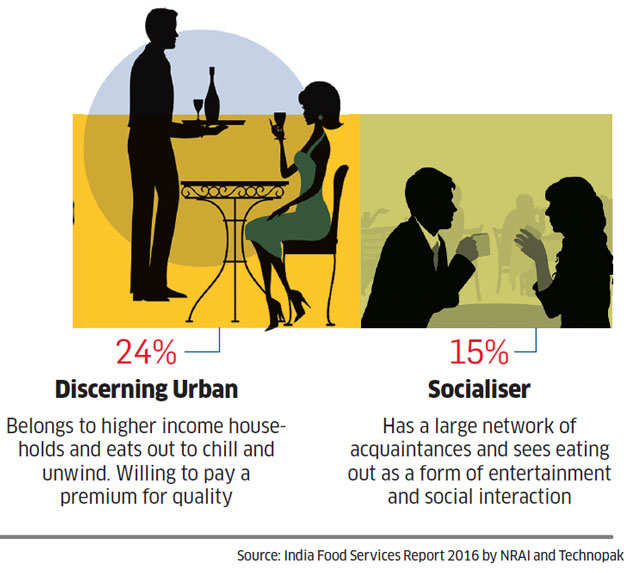

Priyank Sukhija, a Delhi-based food entrepreneur, runs several bars and lounges, including Lord of the Drinks and Tamasha in Delhi and Mumbai. “Lights, music, food, wine… standalone restaurants provide an experience that QSRs fail to do,” he contends.

Standalone restaurants and cafes, says Oliver Mirza, CEO of Dr Oetker India, a consumer foods company, provide wellcurated experiences to consumers at a cost marginally higher than QSRs. Restaurants like Big Chill and Cafe Delhi Heights have pulled in consumers in the metros, and smaller standalone cafes are doing this in smaller cities.

Mirza believes that people are spoilt for choice, which has resulted in reduced loyalty to QSR brands. Consumers are ready to pay extra for a fine-dining experience. As the price gap between fine dining and QSR comes down, some are switching to the former.

The writing, clearly, is on the wall for the QSR players: innovate or perish.

Until 2012, there was no such thing as a product innovation in the QSR industry, as most of the resources were focused on operational efficiencies. McDonald’s last innovation might have been the McAloo Tikki way back in 2004; even today an average outlet of McDonald’s sells about 750 McAloos every day. KFC introduced Cheeza, a chicken pizza, last year and sold over 3.6 million units in just six months. “QSR chains will have to work harder to keep growing. They need concentric circles of innovations,” says Jaspal Sabharwal, a food and private equity industry veteran.