Chaat is often touted as the best example of India’s street food. However this reputation often obscures the fact that chaat is a product of Delhi and Uttar Pradesh’s composite culture — a collage of many home-style dishes of different communities that made up the Ganga-Jamuni culture of Shahjahanabad, and of other provincial (as also courtly and colonial) towns of the Indo-Gangetic plains.

Take for instance the dahi vada. Papdi chaat may be what you now eat off the streets. But dahi vada and its cousins, the dahi gujiya (stuffed with dry coconut, dried fruits and seeds like chironjee) and dahi phulki, are more traditional homely chaats, enjoyed as treats on festivals as diverse as Holi and Eid.

The tradition of fried lentil vatikas (vadas or badas) soaked in milk or yoghurt is an old one. It finds a mention in the 12th century Chalukya text Manasollasa. It is not hard to see dahi vada as a continuation.

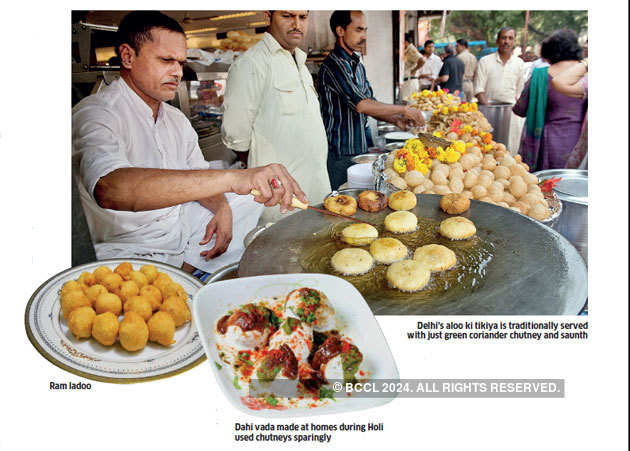

Dahi vada invariably made an appearance during Holi in several households. It was deemed a fun spring treat, where delicacy was prized and home cooks took pride in secret techniques to mix urad dal that resulted in the lightest dumplings possible. This was before baking soda was commonplace, when aeration of the batter was achieved by just beating it right.

There was no indiscriminate dumping of chutneys in the dahi either. Roasted cumin powder and rock salt were judiciously sprinkled, then a hint of saunth, made from either dried tamarind or dried mango powder. The moong dal pakodi, similar to a lentil dumpling, is the predecessor of the Delhi street-eat Ram ladoo. This is a snack that is fried crisp and crunchy on the outside but soft inside. It is eaten with fresh coriander chutney, or dipped in yoghurt to make phulki, eaten on Holi and iftaar alike. However, its most unique manifestation was the use of fermented carrot kaanji, made at the onset of spring. You may still find a few vendors selling kaanji-vade in old Delhi, but this is disappearing.

As chaat made its transition from homes to pattals (plates made of dry leaves) retailed by khomchawallas, newer innovations seem to have set in. One of the oldest form of mobile restaurants, khomchas were cane baskets in which ingredients for chaat were kept. Khomchawallas carried these strapped to their shoulders, typically arriving in a neighbourhood late in the afternoon. They would stop outside homes, offering piquant evening snacks to women and children in days before eating out in restaurants was common.

While researching for my books Mrs LC’s Table and Business On A Platter, in which I talk about the earliest forms of restaurant retail in India, I found out that old-Delhi families still remembered their favourite khomchawallas. It was also a time when being a “chatora” (associated with chaat; loosely meaning someone who likes sweetsour lickable flavours) was looked down upon as frivolous and wasteful. Khomchawallas gave way to mobile carts, then to hole-in-the-wall chaat stalls and now to chains like Haldiram’s. In the process, however, several nuances seem to have been sacrificed, not the least, the ecofriendly idea of eating off saal leaves.

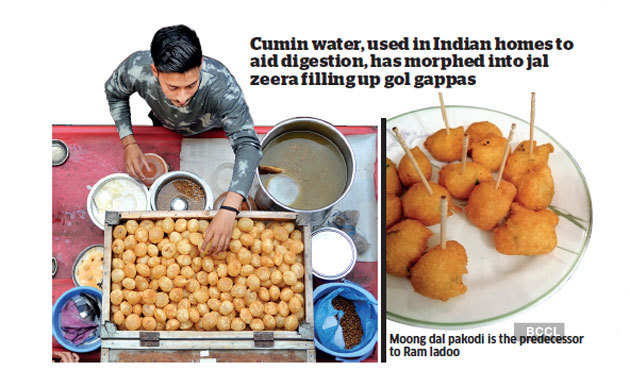

The biggest evolution was in terms of chaat masala, which morphed from simple bhuna zeera-rock salt combine to recipes combining multiple spices. If you are a connoisseur of chaat, you may realise that chaat is really not about dahi-saunth-chutney. In fact, nuance comes from chaat masala and any chaatwallah worth his salt has a unique combination. Though packaged masala has changed that. The distinctive taste of Delhi’s kulle (fruit cups filled with chickpeas, flavoured with lime and ginger) comes from kala chaat masala, rich in pepper, a throwback to a time when chillies were not common. UP chaats don’t use this black masala. Cumin, however, was a main component of any flavouring. According to Ayurveda, it aids in digestion. Its increased use in spring (since chaat was a spring and summer thing) was possibly to kick start sluggish digestion after winters.

According to Ayurveda, the fire element is at its lowest in winter, thus digestion and appetite are poor. In fact, cumin water has always been used as therapy in Indian homes — its morphing into jal zeera filling up gol gappas does not seem that surprising when we see it in this context.

Finer ways of adding texture or more sophisticated taste have lost out to corn flour and sweetened yoghurt. Delhi’s aloo ki tikiya, typically with a stuffing of ground chana dal, is now to be found only in a few shops. Traditionally, it was neatly cut in two halves and served with just green coriander chutney and saunth — no yoghurt or raddish! Fine paani ke batashe in Lucknow were judged to be made from atta not sooji (that puchkas are typically made from). Sooji or semolina was considered more provincial — since atta was the finer ingredient, making for thinner shells.

The epitome of sophistication was Lucknow’s matara, boiled white peas, made into a crisp patty on the tawa, almost like a faux shami kebab. This was typically served with just lime juice and slivers of ginger by chaatwallas who took pride in their art. I went back to the city after decades, specifically to King of Chaat, the fabled snack stall of the 1990s whose owner was once reputed to be an income-tax payer. It was quite empty. However, the old chaatwalla retained his sense of superiority, scolding a new customer for seeking dahi and saunth on matara.

Some tastes still abide.